We brought Daniel to a new psychiatrist recently to consider medication changes that may improve the erratic and compulsive behavior so limiting him right now.

Taking Daniel anywhere these days is dicey, especially an untested environment like a new doctor’s office. His group home director brought along two additional aides to assist in the event Daniel became agitated.

To our collective relief, however, he did great, sitting calmly during the consultation, and only occasionally asking me for “car.” The doctor ordered a complete blood work up before any medication decisions are made, and after visiting with Daniel for a while, I drove the hour and 40 minutes back to Illinois.

My church’s newsletter was waiting in the mailbox when I arrived home, the Focus on Health segment revealing that May is “Mental Health Awareness” month.

I thought back to our appointment a few hours earlier, when the new doctor compiled a medical, behavioral and family history of my son.

“Have you or Daniel’s father ever experienced any mental health issues, like depression, anxiety or inability to cope?” he asked.

I paused for a moment, then answered as succinctly as I could.

“Yes to all,” I replied. “For 20 years.”

I doubt this was the response he expected, but the doctor seemed to understand me: it is depressing, anxiety-producing and difficult to cope, acknowledging that your child’s disability, with its continual challenges and heartbreak, will be lifelong.

The newsletter article I’d begun reading quoted a faith-based mental health professional: “Faith gives me a sense of perspective and teaches me that life is full of seasons. Whatever I’m going through is temporary and will pass.”

How often have we all heard that well-meant platitude: This too shall pass?

But what if it doesn’t?

That question has haunted me for 20 years, since the winter morning in 1994 when a therapist told me, unsparingly, that my son would never be normal.

My faith in things “working out for the best” took a serious hit in the years following that pronouncement. Denial protected me for a while, but eventually I conceded to the truth: Daniel’s life, and my own, were irrevocably affected by autism. He would never be normal. This would not pass.

I wish I could be a person able to profess “this too shall pass” and actually mean it. I guess it is most honest to say that I believe in the phrase in principle, and recognize that in most cases it applies.

But 20 years of “autism management” have taught me, as it has countless other parents, that even during periods of relative calm, the next challenge, or crisis, is forever lurking, out of sight but never out of mind.

The last few years have been consistently stressful where Daniel is concerned, and I recognize that my exhaustion colors my perception right now. But the unalterable fact remains: autism is not a difficult “phase” or period to be endured temporarily, until we get to the other side.

Especially now, during a long-running period of daily strain, it’s a hard sell to dub Daniel’s condition as simply a season of his life, which, like all difficult periods, will eventually subside. We will never stop worrying about him, or dealing with autism’s cruel consequences.

Despite my well-honed cynicism, I finished reading the article, written by my church’s lay minister of health, a woman I’ve known and respected for 30 years. The segment talked about resilience, defining it, in simple terms, as adapting well in the face of adversity.

And I suppose I have been resilient, although the “adapting well” part is open to debate. It’s been painful learning to live with an uncertainty that is actually a certainty: we don’t know what the next challenge for our son will be, but we do know that further challenges, possibly severe challenges, lie ahead.

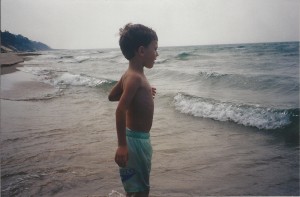

I’ve learned to appreciate the moments, though, within the larger scope of autism, which bring relief, or comfort, or sometimes pure, unadulterated joy.

We were all anxious about Daniel’s own ability to cope with the new doctor appointment that day, fretting in advance about his reaction to a situation that could potentially result in an ugly scene. It has happened many times before.

But that day he did beautifully. Even when a nurse was brought in to take his blood pressure, and the staff held their breath in anticipation of a rebellious outburst.

Instead, Daniel removed his jacket when I asked him to, and without prompting held his bare arm forward, calmly allowing the nurse to wrap the pressure cuff around his bicep. He even picked up the squeeze bulb and handed it to her, uttering his multi-purpose word, “Dauh,” to encourage her.

I was so proud of him in that moment. It was a good moment, within a larger season of moments, that we will get through, one at a time.